first written March 2000; updated 2022

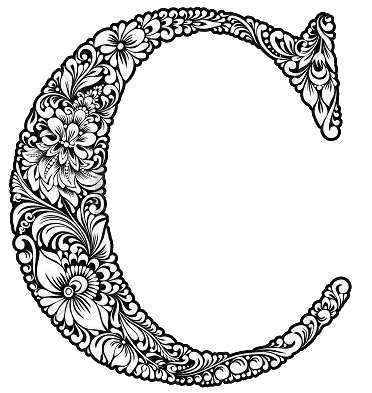

"I just had one of the most rewarding meditations in my life this morning. The letter 'C' opened up for me." My father was driving late one evening, and I was riding. I looked at him. The lines of his face reminded me of Leonardo da Vinci, whose self-portrait looks like an older, long-haired version of the same face. There is an earnest solemnness about his face, I thought, as he looked with seriousness into the dark night ahead. "I mean," he continued, "it's opened up for me before, but never like this. I've been working on this one for 26 years."

"I just had one of the most rewarding meditations in my life this morning. The letter 'C' opened up for me." My father was driving late one evening, and I was riding. I looked at him. The lines of his face reminded me of Leonardo da Vinci, whose self-portrait looks like an older, long-haired version of the same face. There is an earnest solemnness about his face, I thought, as he looked with seriousness into the dark night ahead. "I mean," he continued, "it's opened up for me before, but never like this. I've been working on this one for 26 years." This short article is the first time any reference to the English Kabbalah has appeared in print. My father will not write anything about it on paper. This constraint is coincidentally the same as that developed by ancient Hebrew Kabbalists, who learned and transmitted their knowledge in spoken form only. I say "coincidentally" because he did not copy this aspect -- he learned it independently, during the process of attempting to write a book about Isaiah. In a story told elsewhere, he eventually discarded the manuscript, gaining a sense that he was not to write about his insights. Writing interferes with the delicate threads of contemplation which comprise the insight process. As my father frames it, writing sets up a type of ‘idol' which makes it hard to receive new insights.

This short article is the first time any reference to the English Kabbalah has appeared in print. My father will not write anything about it on paper. This constraint is coincidentally the same as that developed by ancient Hebrew Kabbalists, who learned and transmitted their knowledge in spoken form only. I say "coincidentally" because he did not copy this aspect -- he learned it independently, during the process of attempting to write a book about Isaiah. In a story told elsewhere, he eventually discarded the manuscript, gaining a sense that he was not to write about his insights. Writing interferes with the delicate threads of contemplation which comprise the insight process. As my father frames it, writing sets up a type of ‘idol' which makes it hard to receive new insights. This is an important point to understand, because my father himself doesn't know his own place within the context of others in history who are most like himself. He truly is a solo artist. This fact lends credibility to his discovery in a curious way: He seeks the truth as an end, not as a means to an end, as could be the case if he were publishing his work, making money, or reputation, or in some other way benefitting. This is just something beautiful he contemplates. He says it began when he once prayed: "Show me the hand of God," not knowing what the answer would be.

This is an important point to understand, because my father himself doesn't know his own place within the context of others in history who are most like himself. He truly is a solo artist. This fact lends credibility to his discovery in a curious way: He seeks the truth as an end, not as a means to an end, as could be the case if he were publishing his work, making money, or reputation, or in some other way benefitting. This is just something beautiful he contemplates. He says it began when he once prayed: "Show me the hand of God," not knowing what the answer would be. It began with the letter C, earlier in the evening, as I mentioned earlier. The conversation covered many topics. By the time we got to the restaurant, the conversation had turned, as it often does, to the work of Jesus Christ.

It began with the letter C, earlier in the evening, as I mentioned earlier. The conversation covered many topics. By the time we got to the restaurant, the conversation had turned, as it often does, to the work of Jesus Christ.Conversation on the English Kabbalah

"...that's what the word heathen means. It refers to a person who only wants a portion of what God has to offer. It's like you're a billionaire. Someone approaches you and asks for your help, and you're willing to give them anything they ask for in abundance. Yet they hold out a thimble. They may be a seeker, but they don't want much. It's something we have to overcome if we want to receive the fullness of God. That one you described [the Canaanite woman] is the Girgashite2. Another one with that characteristic is the Hivite. Both have a tendency to want little things."

By this time, it was clear that I was writing what he said. I asked him to repeat a line. He responded, "I'm trying to give you a vision and you can extract from it what you want." I shook my head: "I'm not writing it for myself, but so that others can read it. I can get the vision, but others may want the verbatim information, so that I'm not in the way." He paused, then continued.

"One of the problems of presenting this kind of knowledge is that if people are not ready to receive it, it looks like gobbledygook. A person has to be hungry. A person has to come to the realization that what they're doing in mortality is not fulfilling. Most people don't realize that. Trouble is, most people die before they realize it." He mused while I wrote.

"Everything belongs to a seeker. There is nothing that a seeker cannot obtain. A lot of people go around, frustrated, depressed, confused, it doesn't bother them."

"Everything belongs to a seeker. There is nothing that a seeker cannot obtain. A lot of people go around, frustrated, depressed, confused, it doesn't bother them." "'Chr,' 'C,' is the center, or the heart." He was pleased to return to the letter whose powerful significance was still washing through his awareness. "I found it when I finally asked, 'where is the throne?'"

"'Chr,' 'C,' is the center, or the heart." He was pleased to return to the letter whose powerful significance was still washing through his awareness. "I found it when I finally asked, 'where is the throne?'"

Afterword 1: On graduating from Kabbalah

That's it, that's all I captured of the conversation that evening. It is now 23 years later, I'm 54 and my father is nearly 90. I continued studying in the scholarly method after I wrote this brief article. Although my understanding of the Kabbalah, both the English and the ancient Hebrew one, is more mature now than two decades ago, it is also something that I no longer consider in the reverent manner that may be evident in this small article. This triggers the journalist in me to write about his life's work. Even though I have sinced moved in another direction, I collected notes over the years, and plan to eventually bring them together into some form of pamphlet or book. But for now, this present article is all I have.

This triggers the journalist in me to write about his life's work. Even though I have sinced moved in another direction, I collected notes over the years, and plan to eventually bring them together into some form of pamphlet or book. But for now, this present article is all I have.Afterword 2: From a recent email talking about all this

...That reminds me of something in line with what I was just writing above. It's an idea that my father pointed out. I don't know how much you know about his analysis of language, so I'll give a brief summary: Although he "dropped out" of the modern era when he left California in the 60s, and it seems he did little with that gifted mind afterward, my father did not waste his great intellect.

At first he worked on a book about Isaiah which would have been significant if he had completed and published it. (Over the years, I have researched numerous writers on Isaiah and my father's insights are more penetrating than most). But that was not to be; in a story told elsewhere, he eventually threw away the manuscript. Nevertheless, he continued with his study of Isaiah, developing deeper insights than he would have arrived at if he had published.

He would read ten chapters each weekday, and then all 66 chapters each Saturday. He did this throughout my early childhood. I have tried numerous times to do something similar, and consistently find myself frustrated and give up -- thus I know firsthand how Isaiah is difficult to understand. It was a significant exercise of intellect for my father to study Isaiah as much as he did. This laid a foundation for what came next.

In the mid-1970s, he began to develop a curious, intricate, and increasingly profound insight into language. It is centered on a beautiful internal structure that, when operated by rules which are logical, grammatical, and mathematical in nature, reveals, like a diamond turning in the light, facets of hidden inner truth.

In my father's view, language has a deep, hidden, inner structure, and he developed a way to access that structure through meditation. You said that when you travel, you don't turn on the radio, you just think. In a similar way, my father was always thinking on these kinds of things. Always. He was largely absent as a father, even though he was physically "there," because his mind was on other things.

Of course, this was hard on my mother, who raised us for the most part single-handedly. I understand most kids grow up with a father who is not very attentive to them -- this is a common theme in movies and books and songs. I’m thankful we didn’t experience abuse, or problems like alcoholism, affairs, or anything like that. As you noted, my father has always been a kind person. But frankly, he loved his meditations, work, and other projects more than he loved his children.

Over the years, I've noticed that I am more like my friends whose parents were university professors, than my friends whose fathers cared for them in a more directly meaningful way. A few of us inherited the trait of thinking all the time from him. Several of my brothers and sisters could care less about his meditative inquiries. Be that as it may, this study of language occupied his mind for decades.

What he developed eventually grew into a mature, coherent, work which compares nicely with similar well-documented efforts by others over many centuries. Few understand what he accomplished. He's not good at communicating it in a way that makes sense to the ordinary person. At that level, it's a parlor trick: "Hey, did you know I can analyze your name and tell you what it means?" However, I have deeply researched the historical context of his ideas. There's a lot more going on than people realize. So let me talk a little about that.

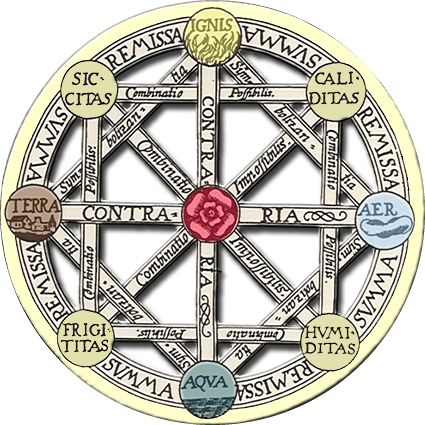

Leibniz drew this while working on the idea

In short, he created4 an implementation of an elusive and intriguing idea about language and truth developed by Gottfried Leibniz 300 years ago. The underlying idea is now legendary to a handful of scholars around the world. Such scholars would find my father's work rather intriguing.

Over the past three centuries, many great minds have studied Leibniz and tried to accomplish what my father appears to have accomplished. Others who have worked on the idea were seeking something Leibniz called the characteristica universalis, Latin for universal character.

He also wrote about a "calculus ratiocinator," a description of what we now know as a computer. He was the first to describe binary logic as it is used in all computers today. People who study his idea called it "The Universal Computer" and some of them eventually ended up creating the first computers.

A computer is a hardware implementation of about one third of the original idea, the "calculating" part. Several of the people who invented the computer were well aware of Leibniz' ideas, and were trying to implement them.

In addition, significant advances in mathematics and logic have come from other people seeking to implement these ideas. Those people were trying to develop something more like what my father discovered. They failed at that, but ended up significantly advancing mathematics and logic while failing at the fantastic idea. Several times this happened.

If the computer is one third of Leibniz' original idea, my father developed a second "third," yet he did so without realizing it. What he created is analogous to the software, while a customized computer provides the hardware.

What my father developed is currently only accessible via meditation, but because it involves a number of key archetypes and a set of logical rules and relationships, it could be implemented in software. It would take some effort, but it can be done.

The final "third" would be constructed out of the best insights of the many deep thinkers who have worked on these ideas for centuries. Inspired by Leibniz, great minds like George Boole, Giuseppe Peano, Georg Cantor, David Hilbert, Gottlob Frege, Kurt Gödel, and Alan Turing have worked on this idea. Although these names are little known outside of mathematics, they are a Who's Who of men who have shaped great advances in math and logic for the past couple centuries. All mathematicians know them well.

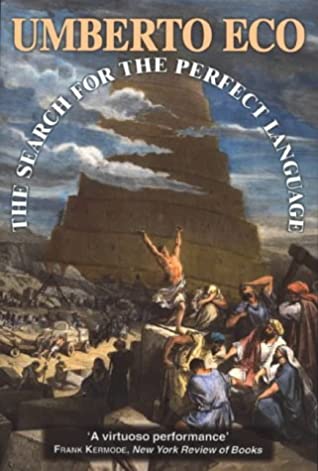

There are others; one of my favorite books in this area is by Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language. He devotes a chapter to Leibniz and follows the idea forward through history from there. His book goes into the linguistic aspect, whereas the famous names above are more associated with mathematics and logic. Along with Eco himself, Jorge Luis Borges would be another well-known name on the linguistic side.

There are others; one of my favorite books in this area is by Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language. He devotes a chapter to Leibniz and follows the idea forward through history from there. His book goes into the linguistic aspect, whereas the famous names above are more associated with mathematics and logic. Along with Eco himself, Jorge Luis Borges would be another well-known name on the linguistic side.

Oh -- and, before I forget, there is one more on the mathematical and logical side: C. S. Peirce independently developed important elements. He is unique in that he did not do this by extending Leibniz' ideas (as far as I know). Instead, he was another Leibniz, a fertile fountain of deep insights across multiple domains. I like his work because of his focus on ternary logic, which has been my own area of study for half my life.

Now here is a startling fact: My father is not aware of any of what I said in the previous paragraphs. I would love to tell him. I have tried many times to break through his inability to listen, but he invariably sees such attempts as a form of competition, and shuts me down before I can say anything like what I've just written.

Consequently, he knows nothing about my passion for ternary logic or mathematics. I earnestly try to share insights with him -- the same way he shares his insights -- and consistently encounter an impenetrable wall. He is "the teacher" and never a student to anyone else, not even to hear this fact alone, which he would receive as a criticism, and dismiss.

I do understand that he had to set up intellectual barriers in order to penetrate deeply in his meditative seeking process -- I inherited a similar ability -- but his version is more extreme. For example, after one of my children taught me something about love which I had never supposed, I began working to keep a door open to my children to "teach" me. He hasn't figured that one out yet.

Ironies abound: My father's favorite professor in college used the Socratic method of teaching. I wish he would, too, but he uses the pedantic style. He can talk for an hour straight on the merits of the Socratic method, but he never actually uses it. It's too bad; there is an embedded humility in the Socratic approach which is not in the pedantic method. When I've tried to use it, I find it really difficult, and soon go back to the model I inherited from him.

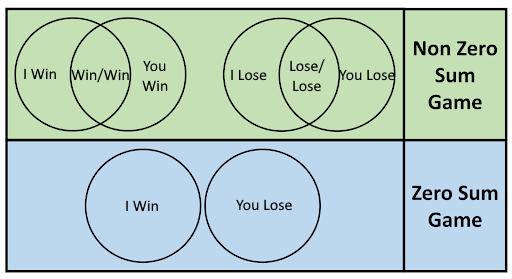

In the language of Game Theory, he plays a zero-sum game. This kind of game uses binary logic, and binary logic requires an "excluded middle." In this way he is more like a computer than a man: analytical, categorical, emotionless, thinking about feeling, talking about feeling... but not actually feeling.

In the language of Game Theory, he plays a zero-sum game. This kind of game uses binary logic, and binary logic requires an "excluded middle." In this way he is more like a computer than a man: analytical, categorical, emotionless, thinking about feeling, talking about feeling... but not actually feeling.

My father will happily admit he does not comprehend love, but if you think that sounds like an open door, it's not. He consistently redirects any conversation on love to an analytical discussion of the word "appreciation," which is an accounting term about increasing the value of something. He loves analysis of that word.

It's sad, because my mother was so full of love that he never comprehended because he doesn't functionally understand what love is -- only analytically. Imagine if you believe of yourself that you know a lot about love -- are you easy to talk to about love?

I have much more to say on this, but I want to get back to Leibniz' idea. I have studied all of the preceding list of mathematicians and logicians as a part of my own journey into ternary logic. My current interest in AI, for example, is one part of this journey. I am convinced that a binary approach to artificial intelligence will forever keep it artificial, so I'm working on the next stage, which I call cyber intelligence.

Cyber is Latin for "governor" so this is a reference to self-governing. Others call this next stage "Artificial General Intelligence" or AGI, but they're approaching it in a binary-logic way, which means they may never get to the "generality" that they seek. Generality is what happens when you remove all the "excluded middles" which separate everything, and that's what I'm working on.

All of that to say, that my dad's insights into the meaning of words are deeper than the average bear.  And, now finally back to your point on giving thanks; what he once observed about "giving thanks" is this: one element of "thank you" is a concept I'll call "transfer of ownership." He said that, until someone says "thank you" for something they received, they do not own it. It still belongs to the giver. Thus, "thank you" is not only gratitude -- a giving -- but it is also a receiving.

And, now finally back to your point on giving thanks; what he once observed about "giving thanks" is this: one element of "thank you" is a concept I'll call "transfer of ownership." He said that, until someone says "thank you" for something they received, they do not own it. It still belongs to the giver. Thus, "thank you" is not only gratitude -- a giving -- but it is also a receiving.

According to him, this insight is embedded in the inner structure of the words "thank you." I've taken notes from time to time of such insights, and someday I'll publish what I've collected. Toward that end, I've attached to this email something I wrote a couple decades ago5. I just went through and edited it to make it more coherent, but I've retained the perspective of when it was written even though I’ve outgrown some things I said. It's a snapshot of the process of his discovery, and what I thought of it, in the year 2000.

You will note the emphasis on "Kabbalah," tightly woven into the small article I wrote in 2000. If I were to write the same thing today, I would likely not even mention that word, focusing instead on the mathematical and logic aspects, more along the lines of what I just wrote. But that's where I was two decades ago, and the article flows well enough I'm leaving it largely "as is."

I also attached a review of a book on some of these other thinkers (The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing), so you can see what I'm talking about from a more objective point of view, if you want. Note that the first part of that review is... dry and targeted to a specialist audience, so skip to the second page, where it gets more interesting with this paragraph:

In The Universal Computer Davis begins his tale with Leibniz, whose proposal for an algebra of logic is the point of departure on the road to the universal Turing machine. It is indicative of the enthusiasm with which Davis infuses his writing that where others see "fragmentary anticipations of modern logic", Davis perceives "a vision of amazing scope and grandeur." As Davis tells the story, Leibniz "dreamt of an encyclopedic compilation, of a universal artificial mathematical language in which each facet of knowledge could be expressed, of calculational rules which would reveal all the logical interrelationships among these propositions. Finally, he dreamed of machines capable of carrying out calculations, freeing the mind for creative thought." The chapter is called "Leibniz's Dream", and that dream is a sort of North Star toward which the axis of each subsequent chapter points.

That is the larger historical context in which my father's insights were born.

Having matured since I wrote the article at the turn of the millennium, I see that I admired his work without much critical thinking. I see things in a more balanced way today. I do not want to glorify the work of my father too much, both for the reasons explained above, and because of some mental illness issues which troubled four of his nine children, including me, some of us for years.

This is a variable in the same elaborate formula which forged his insights, a very relevant one which should not be forgotten: Could my father have discovered these things if he had been a better father, learning how to love his children rather than the hidden structure of language? Possibly not. The future will reveal whether it was worth it or not.

Certainly, history is filled with examples of this same story: for example, look at how the miracle of Mozart was created as an extension of his father’s ego. I think I can be grateful that I didn’t receive that inheritance, but I do love and thank God for the music which came out of that crucible, nevertheless.

I am confident the solution to the disconnect here is what I have devoted myself to; it is found in ternary logic, which is the logic of "included middles" and therefore the logic of love -- a positive-sum game; the art of embracing, not dividing and competition which happens in zero-sum games.

I am confident the solution to the disconnect here is what I have devoted myself to; it is found in ternary logic, which is the logic of "included middles" and therefore the logic of love -- a positive-sum game; the art of embracing, not dividing and competition which happens in zero-sum games.

Back to the original subject of gratitude, I'm grateful that I have young children who are teaching me what love is, to whom I am learning to listen in the ways that I always desired from my father.

Footnotes:

1. This is an idea famously explored by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wrote about "things which cannot be said" about a century ago. At the time I originally wrote this short article, I had not yet studied Wittgenstein, or I would have made a reference to him at this point.

2. Girgashites and Hivites are two of the seven Canaanite nations that lived within the borders of ancient Israel, who represent seven "temptations" of the seeking process of spiritual growth.