Well, well, well. I am delighted to find yet another piece of private intuition has a respectable home already existing in the public domain. I've been working on this insight for years, but not able to put it into words well enough to relay it to others coherently. Much to my delight, I find that Schrödinger already had the same observation, and saw it more clearly than me, though apparently not many realized the importance of what he was saying.

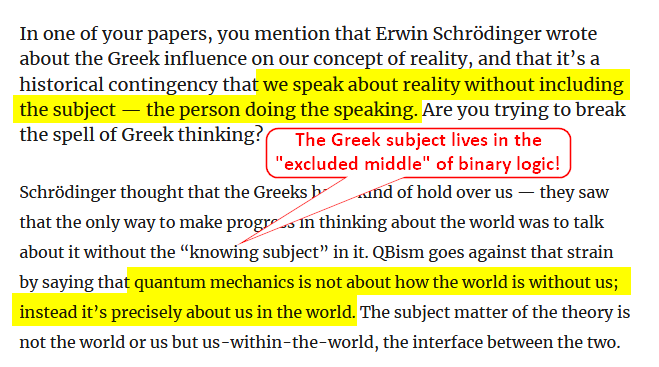

I was reading an article about the rather interesting angle on a new quantum theory called "Quantum Bayesianism" when I came across the following quote. I screenshotted and annotated it immediately, as I do with such things.

As you may know, I've been studying ternary logic for a long time now, and have written often about a particular tiny flaw in binary logic, which first arose in Greek thought. I've been able to trace the flaw within mathematics and logic back to Aristotle and Euclid's original "dimensionless point" concept. They had a good reason for defining this -- on the surface, it appears to solve a certain problem with measurement and everything works intuitively once you accept the fact that math exists in a different world than common everyday reality. But the assumption causes other problems, which took centuries to identify because Euclid and Aristotle's insights worked so well.

The flaw is cleverly hidden, but once you see it, you begin to see it everywhere because... it is everywhere. It is hidden by being embedded in the definition of binary logic -- not in its postulates or axioms, but deeper, in its first underlying assumption. Although it is plainly right in front of us, we don't understand that, in order to accept it as true, we have to accept the existence of something that doesn't exist... and this is where things begin to go wrong.

I knew that the logical flaw had huge consequences, because so much is dependent upon this form of logic (for one example, as is well known, computers operate at their most fundamental level using this logic). But I had a hard time figuring out what was the valuable thing being left out of binary logic, partly because I was using binary logic to contemplate ternary logic. It was years before I even realized I was doing this, and began seeking to understand ternary logic on its own terms. It was still more years before I was beginning to make real breakthroughs in this area. I'm not smart enough to figure this out myself as if I were someone like C. S. Peirce. Rather, I'm better at noticing a binary paradox when it is exposed by others (who usually have no idea how it's related to the structure of binary logic), and then contemplating it. I do this one piece at a time, slowly building an internal database of seemingly unrelated pieces that each show a different facet of this problem.

Now I see this one, and it's a big one. In order to make binary logic work, we have to move the stuff that normally fits into the "excluded middle" (i.e. whatever naturally exists between True and False) somewhere, because it no longer fits in the excluded middle. Until now, I thought the shift was a subtle one, where we simply started subtly emphasizing how we related to some things and de-emphasizing others, with effects that grew incrementally over time (very hard to research), but now I see we shifted ourselves* out of logic and math. And we lost track of the shift. We began thinking of the world as an external system, contemplated by a subject which had no relation to the external object except as an observer discovering "laws" and "principles" which guide the external world (and by extension, ourselves).

In fact, we are very much actors who are intimately involved in what we're contemplating. Only in the past century have we discovered quantum physics which forced us to put our consciousness back in to the mix of things. However, we are continually baffled by this realization because we've become so accustomed to thinking that... well... that we don't exist, except as abstract observers of the world.

*This point is unfinished because I have other things I need to do now, but I think the point about judgment in this StackExchange article is relevant here. Did ancient Greeks shift the act of judgment? I think we did, and Frege noticed this when he made logic more rigorous.