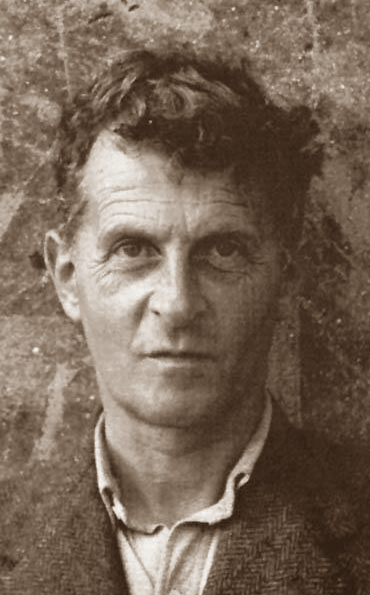

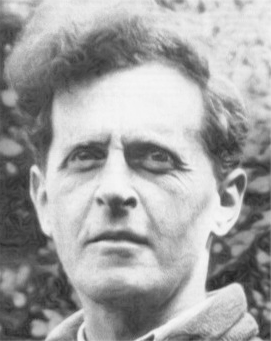

I just confirmed a hunch using Wikipedia in the manner where it excels: providing well-known facts which are not controversial. My hunch was that logical positivism traces directly back to the deep insight Wittgenstein introduced as the concluding statement of his Logico-Tractatus, where he makes a clear distinction between things which can be said and things which ought not be said (because they are talking about the realm of what is fundamentally unspeakable). Thus to speak of them is a form a nonsense, and it is better to say nothing.

I just confirmed a hunch using Wikipedia in the manner where it excels: providing well-known facts which are not controversial. My hunch was that logical positivism traces directly back to the deep insight Wittgenstein introduced as the concluding statement of his Logico-Tractatus, where he makes a clear distinction between things which can be said and things which ought not be said (because they are talking about the realm of what is fundamentally unspeakable). Thus to speak of them is a form a nonsense, and it is better to say nothing.

Indeed, Wikipedia says: "Logical positivists picked from Ludwig Wittgenstein's early philosophy of language the verifiability principle or criterion of meaningfulness" right at the start of its discussion of the origins of logical positivism. So therefore this is common knowledge, which is good. Maybe you knew that already.

It's good, because the next half of my hunch has to do with how Wittgenstein's original point got lost in the nonsense we know as logical positivism. Wittgenstein wanted nothing to do with the positivists who latched on to his penetrating insight, because he knew they were literally speaking nonsense exactly as he said not to. But he also knew if he said a word on this, he would be contributing to the nonsense, so he remained silent.

He best exemplified this by the well-known scene where he attended one of their discussions (the Vienna Circle), then sat in a chair facing a blank wall, opened a book, and began reading something from ancient Sanskrit. He was saying "I'm speaking nonsense" without saying it. He was "showing" them -- not "saying" to them -- "showing" them that they were speaking nonsense... by speaking nonsense.

None of them got it.

I've encountered this curious scene narrated at least a half-dozen times if not more, as it is recounted often by people who write about Wittgenstein, but I've not yet seen anyone interpret it in the way that I just did. I'm sure in the wealth of thousands of papers on Wittgenstein, others have made the observation, but I haven't yet encountered them yet. As you can see by my looking up this simple fact using Wikipedia[1], I'm a beginner on the subject, so I may eventually find this observation made by others.

Living what you believe

What excites me about Wittgenstein is that he "lived" what he believed, instead of just believing it and living by a different set of principles, which is a dual-minded behavior that makes a mess out of philosophy (and religion too, if you understand the words of St. James, who talked about how "a double-minded person is unstable in all of their ways").

Within the realm of philosophy, it's too easy to wander off into elaborately-woven intellectual incoherence this way: if you aren't living what you believe, there is a very good chance what you believe is sophistry which doesn't actually function that way when applied to real life. It took me a long time to figure out this point, which I did only because I inherited a healthy dose of this exact problem without having any idea of the inherited cognitive dissonance. Thus I spent years believing things that I did not live, and living things I did not believe. This consistently ended with catastrophic collapses as the two worlds collided.

However, over the past couple decades, I've been working consistently to align these two domains, in small but steady increments, as I pursue an arc of self-discovery and ever-increasing other-awareness, getting free from that double-minded "unstable in all their ways" lifestyle which I learned as a child. I see it as a process of integration, as compared to the inherited disintegration which was happening before I started on this path.

I've known for years that this is one of the key aspects of my own writing, what makes it different from others who may write on similar subjects or in similar ways. It is a limitation and it is a gift, simultaneously, so I won't paint the joys or the sorrows here. Please understand I say this knowing that this aspect of my writing is a work in process, and I have much further to go. I have no aim to perfect this art within my lifetime, but only to move the ball a little further down the field from where it was when I found it -- now that I know what the ball is, where the end goal is, and how to move across the field... all of which I didn't know when beginning this journey so long ago.

In this respect, I recognize Wittgenstein was doing a similar thing at a more expert level. Let me give you a very clear example of what I mean so you understand the point:

The logical flaw of identity is...

Alfred Korzybski is also one of my intellectual heros, because of his penetrating insight into the logical flaw of identity, where he notes that the verb "to be" or, more familiarly, the word "is" contains a logical flaw where it is asserting an equivalence -- identifying one thing as equivalent to another -- which is NEVER true. He goes on into the famous "the map is not the territory" and other colorful insights, but the essence of his point is quite simple:

We should stop using the word "is." Doing this improves communication immensely, which, um, basically leads... inevitably to World Peace.

If you study Korzybski much, you'll soon find there is a small group of people, mostly scholars, but also some normies, who have developed a way of speaking which respects this logical insight. They don't use "is." But ironically, Korzybski himself never really applied this insight in his own life. He continued to use the verb "to be" in all its flavors as a normal person would, to the end of his years. So, he has this penetrating insight, writes a massive (and surprisingly influential, for something you've likely never heard of) book about it, and then doesn't apply it in his own life. This is a textbook example of the point I'm making, about believing and doing.

If you study Korzybski much, you'll soon find there is a small group of people, mostly scholars, but also some normies, who have developed a way of speaking which respects this logical insight. They don't use "is." But ironically, Korzybski himself never really applied this insight in his own life. He continued to use the verb "to be" in all its flavors as a normal person would, to the end of his years. So, he has this penetrating insight, writes a massive (and surprisingly influential, for something you've likely never heard of) book about it, and then doesn't apply it in his own life. This is a textbook example of the point I'm making, about believing and doing.

...a mistake which Wittgenstein didn't make

And it is an example of what Wittgenstein did fundamentally differently. In fact, he did the opposite. Wittgenstein did what he believed. You can see it in how one of his first big steps into the world of "showing" rather than "saying" was to reject an enormous inheritance that would have made him a wealthy man beyond the imagination of even most wealthy men. Have others noticed this? I only realized it the other day: By such steps, he was "living" what he believed, not just believing it and talking about it.

I wonder if others have made the connection with Henry David Thoreau, who also did a similar thing a century earlier, or Tolstoy, who initially kept his wealth but openly shared it very generously with the poor, for example by setting up schools and personally getting involved in their lives in ways that were exceptional for a wealthy person. There are others throughout history who have done similar things. Gandhi did this, too, and of course Jesus very tightly integrated his words and actions, and Diogenes in ancient Greece was famous for this as well, so I know the concept is not entirely new. I just think that it's an aspect of Wittgenstein's story that I haven't yet encountered as a topic of research, as I continue to learn more about him.

So when the logical positivists founded a new branch of logic on his insight about what is and what is not meaningful to talk about -- but they completely missed the point that he was making -- he was forced by his own adherance to principle not to talk about it. By then, he was already well along the path of making a sharp distinction between saying and showing. With his life, he was showing people how this worked. He couldn't "say" anything about what he was doing, because he was so rigorously holding to the "showing" way of communicating. In other words, if he had said anything more, even one sentence more, than the Logico-Tractatus, he would be betraying the principle that he had just elucidated. (You'll see further down this essay that he wrote about this very point, in other words "writing one sentence more", and you can even see this struggle, about whether he should even write what he was writing, in his words at that time.)

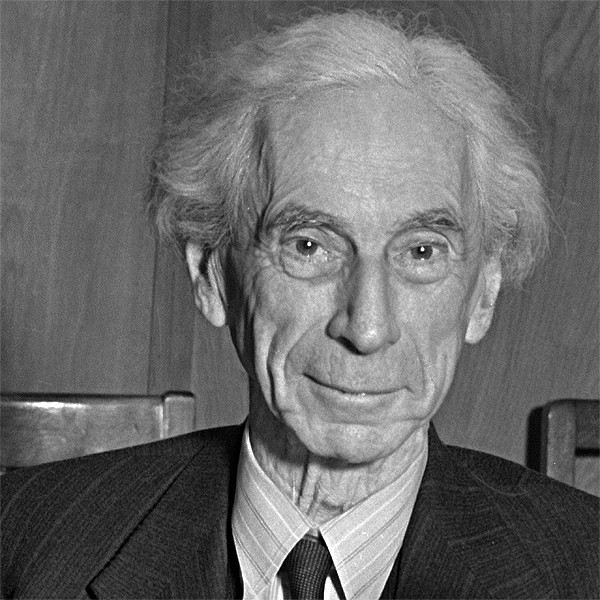

He didn't betray himself. I can imagine him pacing and forth in Bertrand Russell's living room in the middle of the night, fretting over how to communicate that the positivists were getting everything wrong -- without saying so. (Russell writes about times when Wittgenstein would do that, pacing back and forth for hours, wrestling with some philosophical idea or another, sometimes to a point of being completely silent for hours at a time. Once time, Russell asked him "Are you thinking about logic or sin?" because these were two dominant themes in such discussions, and Wittgenstein, who had not said a word for more than an hour, answered simply: "Both"). Reading such intimate stories and seeing how Russell writes about him, I get the sense that Russell never quite understood Wittgenstein, although clearly they knew each other very well and had many discussions. The two prefaces I've seen, where Russell writes a preface to Wittgenstein's books, give solid clues, at least to readers like me, that Russell didn't quite understand Wittgenstein. (Update: I've since read others making the same observation, so it's fairly well known.)

He didn't betray himself. I can imagine him pacing and forth in Bertrand Russell's living room in the middle of the night, fretting over how to communicate that the positivists were getting everything wrong -- without saying so. (Russell writes about times when Wittgenstein would do that, pacing back and forth for hours, wrestling with some philosophical idea or another, sometimes to a point of being completely silent for hours at a time. Once time, Russell asked him "Are you thinking about logic or sin?" because these were two dominant themes in such discussions, and Wittgenstein, who had not said a word for more than an hour, answered simply: "Both"). Reading such intimate stories and seeing how Russell writes about him, I get the sense that Russell never quite understood Wittgenstein, although clearly they knew each other very well and had many discussions. The two prefaces I've seen, where Russell writes a preface to Wittgenstein's books, give solid clues, at least to readers like me, that Russell didn't quite understand Wittgenstein. (Update: I've since read others making the same observation, so it's fairly well known.)

Moving from "saying" to "showing" takes years

Anyway, I'm getting a little afield of the point I wanted to make when I started, which is that the positivists created such a mess out of Wittgenstein's insight that they obscured what he was trying to do. I want to do what I can to retrieve his gem from the murky miasma they created. At this early stage, I have read a fair amount about Wittgenstein, but I have not yet read his own writing, which I now look forward to. So I do not expect you to take my thoughts here too seriously.

Also, I've definitely been wrong about Wittgenstein before (I first encountered him as a side character in a biography of Kurt Godel, whose biographer... didn't like him), and later came around to see that there was more going on with Wittgenstein than it seems on the surface.

Wittgenstein's insight that there is a realm of things which cannot be spoken came into my life over the past year as my own personal journey crossed over a certain threshhold which kind of embodies that insight. I've been preparing for this transition for years, easily more than a decade, without quite knowing how it would appear, and sometimes thinking it had already arrived, because I didn't have the language yet to understand it... until I encountered Wittgenstein's ideas, and I finally had words to my experiences: I slowly realized that I was moving between the "saying" world into a "showing" one, on a large scale. The transition between the two domains is a several-years-long process which I'm in the middle of, so it's not yet easy to write about some aspects of it, but the events in my life over the past year have definitely captured this theme well enough for me to have developed a great respect for Wittgenstein's framing.

Those who do what they believe carry more depth than those who simply believe

I do not imagine that other thinkers, who have not yet personally aligned their words and their actions on the level that Wittgenstein embodied, will grasp the idea here in any deep way. They will get only an intellectual understanding, rather than a practical one. For example, one of my ongoing intellectual dialogues is with someone who fiercely resists applying what he believes in his own life, at least, not beyond a certain relatively shallow point. As I was when I was young, he assumes that he is correct without actually living it out. He's a great teacher and friend, but does not do what he teaches, at least not like he used to. I've heard stories of his youth where he did this more, and I wonder what changed.

Being younger than him, I did what he taught, many times, before I realized that I was the only one doing what was being taught. My life was radically transforming, while he was just treading water, refining his ideas but not really going deeper. In fact, over the past twenty years or so that I've been in many conversations with him, he's wandered off his own path in certain distinct ways which now alarm me, because I'm still on that original path he discovered and laid out, and find it to be quite rewarding. The impasse we've reached at this point is heartbreaking, but it also reveals in sharp relief the difference between developing a philosophy on an idealistic level and living it on a practical level.

So this is a point I know very well, with lots of sincere seeking and many iterations behind the knowing. As the gap between us slowly widens, I'm lately learning to not take it personally: to let it go, by simply noting the irony to myself, and letting it happen. This was yet another important step for me which I could not share with him. I fought for years to "keep" my "teacher," but now I see he will remain in his idealistic temple for the rest of his life. He's old and tired, and I understand what needs to be done now enough to go alone.

However, from this lonely promontory where I find myself, abandoned by a teacher for reasons beyond my control and his awareness, I lately find a fellow traveler on this path in Wittgenstein. He reveals an incredibly rigorous adherance to his own principles, knitting words and actions together in a magnificent way, beyond my ability. Admittedly, he came from a better foundation -- his youth and teachers were literally legendary, but with that rich intellectual inheritance, he went futher than his own teachers, and set a high standard in this area, toward which I aim.

People don't understand Wittgenstein was doing what he said to do

Wittgenstein is famous for teaching something completely different in his later philosophical investigations compared to what he wrote in his former investigations. People who don't understand that he had moved into the "showing" phase of his Tractatus think that he was being inconsistent with his "saying" phase, even though he was pretty clear on what he was doing -- for those who were listening. That being said, as I hinted earlier, I will note that it was a tiny slip-up in keeping his own principles which revealed perhaps the best clue into the fact that he knew exactly what he was doing. In 1919, Wittgenstein wrote to Ludwig von Ficker about the Tractatus:

You see, I am quite sure that you won't get all that much out of reading it. Because you won't understand it; its subject-matter will seem quite alien to you. But it isn't really alien to you, because the book's point is an ethical one. I once meant to include in the preface a sentence which is not in fact there now but which I will write out for you here, because it will perhaps be a key to the work for you. What I meant to write, then, was this: My work consists of two parts: the one presented here plus all I have not written. And it is precisely this second part that is the important one. My book draws limits to the sphere of the ethical from the inside as it were, and I am convinced that this is the ONLY rigorous way of drawing those limits. In short, I believe that where many others today are just gassing, I have managed in my book to put everything firmly into place by being silent about it (von Wright 1982, 83).

I bolded the part that leaped out at me for a couple reasons: you can see that Wittgenstein struggled with whether to even say this tiny metadescription of what he was doing while writing the book. In fact, he didn't say it in the preface, but only in a private letter. I puzzled over this: Why would he struggle, and in the book itself NOT say this, and then in a letter to a friend, explicitly say it? It's an absolutely key insight; without it there is almost no way in. As I contemplated what was going on here, I realized that his hesitation, and why he left it out of the book, was this: he knew he was breaking his own principle... by saying something about the showing.

I have pondered this insight into his own writing many times over the past year, and I now feel certain this is (as he noted) the key which unlocks the door to understand what he meant by "saying" vs "showing." I've seen other writers struggling to understand what he's doing with these two different domains, and failing to grasp the point, because they don't look at what he was doing with his life.

Silence is primarily a doing, not a saying

Look again at the second bolded phrase: "by being silent." This is the part he wasn't saying. People who struggle over these two domains do not look at what he was "being." I'm guessing that even before the book was published, he saw this would happen, and that is why he felt he needed to break his own principle and say this in the letter to von Ficker. I wish he would have said it in the preface, but thankfully, it's an oft-quoted passage. Again I note that on several occasions I've seen people quoting it who clearly don't understand the point.

Seen from this perspective, it is obvious that the logical positivists utterly missed what he was saying... er... showing. They got the point that he was drawing a firm border between what can be said and what cannot, but they did not get the point about how to speak in the language of showing, or they would have gone silent, like he did. Instead, they invented a well-described category of things which do not have empirical evidence, and said this is what ought not be discussed. They did not realize what was meant by "showing," which was that they ARE to be discussed, but with showing, not saying. They remained stuck in the saying and never understood the showing, even though Wittgenstein was right there, silently showing them what he meant.

As more people grasp what I'm saying here (again, I understand others may be saying the same thing, but I haven't found them yet), I feel certain there will one day be a Renaissance of Wittgenstein's insight, which is what he originally intended. And it will change the world on the level that he foresaw: deeply.

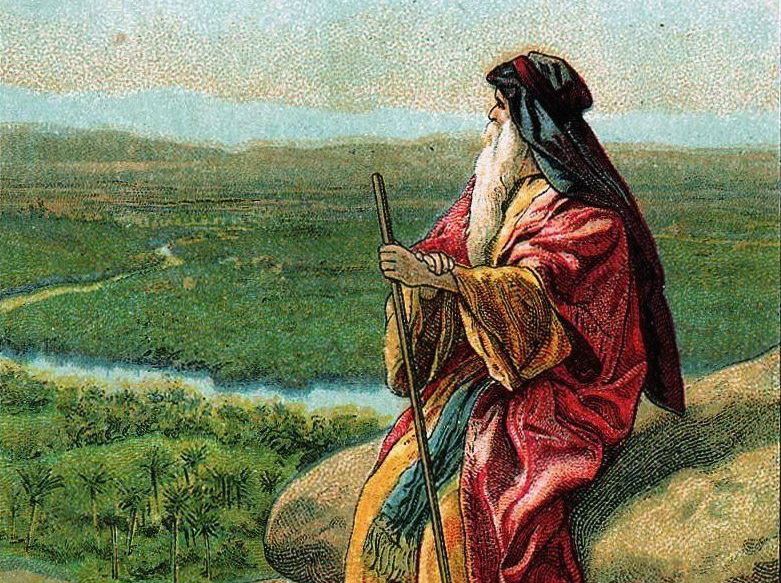

The Promised Land of Wittgenstein

Oh how heartbreaking it must have been for him to see, like Moses on the mountain at the end of his life, the Promised Land, to see it right there before him, and to be unable to touch it. By this, I mean the promised land that every writer seeks -- that one which arises from an audience "getting" what is being written. There can be no greater joy for a writer than this; money and fame are secondary for a writer, at least, one who writes from the heart. But note, this is just the most obvious interpretation: I also mean the deeper Promised Land that I'm increasingly experiencing in my own life, within a context that is bigger than this key insight from Wittgenstein.

Oh how heartbreaking it must have been for him to see, like Moses on the mountain at the end of his life, the Promised Land, to see it right there before him, and to be unable to touch it. By this, I mean the promised land that every writer seeks -- that one which arises from an audience "getting" what is being written. There can be no greater joy for a writer than this; money and fame are secondary for a writer, at least, one who writes from the heart. But note, this is just the most obvious interpretation: I also mean the deeper Promised Land that I'm increasingly experiencing in my own life, within a context that is bigger than this key insight from Wittgenstein.

I'm so grateful for the language that Wittgenstein provides for how to speak of this unspeakable domain, and I don't mean the language in what he wrote. I mean the language of doing, not speaking. As a culmination of a leap of faith I made years ago, the leap is finally bearing fruit, and as a consequence I'm transitioning from a world of saying into a world of showing. As Wittgenstein would be the first to point out, it's nonsense to say much more than this.

Although I feel comfortable writing about the preceding insights which have opened the door to this transition, I already see that there is a whole new world of "showing" which simply cannot be spoken. Not merely should not, but cannot. I'm already experiencing it enough to know it has to be experienced to be understood. And I want more. It is no longer an intellectual idea which sounds good, but it is a way of being that... lemme see if I can put it into words... yup, I succeeded, by way of something fairly poetic. Check this out: the following paragraph from my private journal is nonsense which is nevertheless ironically firmly embedded in sense[2]:

trying to capture a butterfly with a sword

You know that stage you get to after years of daily meditation, where you're finally able to easily move into the condition of letting-go of everything within a matter of minutes, and just being at peace with everything, no matter how hard things may be in the non-meditative state? I don't mean the forced Zen type of letting-go -- a projection of emptiness, which is all too common -- but rather the mature, more comfortable letting-go, allowing oneself to be held in quiescent abeyance in the palm of the vast universe, trusting that the experiences of the day, and of the moment, are all transitory and there is behind everything a vast meaningfulness which we humans are only just beginning to comprehend on its own terms. That state of being which is listening, not speaking. Or even more subtle: That state of being which is just... being. To try and capture it with words is like trying to capture a butterfly with a sword: Only when you hold the sword still, and let the butterfly land upon it, gently folding its wings in that calm, meditative way of being which is completely at one with all of Nature... only then, when the sword transforms from a swinging cudgel into something which is still, and silent, wordless... only then is it clear: if we could achieve this state continually, we would be walking in the Garden of Eden with God again.

Footnotes:

- ^ Nothing against Wikipedia. Especially not the old: 'Wikipedia can be written by anyone so it's not a reliable source of information.' While technically correct, it's pedantically so. In fact, if you use Wikipedia with a bit of common sense, it's a great resource for a much broader base of common knowledge information than any one person usually has at the tip of their tongue. What I meant by the statement for which this is a footnote: I began this article by looking up a simple fact about Wikipedia which any expert Wittgensteinien knows well. I wasn't relaying information from Wikipedia to express how common the information is (as I sometimes do while writing), I was honestly looking up the fact because I didn't know it.

- ^ Ha! There's a pun Wittgenstein was making with the word nonsense, which I only just got, and it's a good one.